Highway construction prompts oak-hickory woodland restoration, archaeological discoveries

Larry Cleverley is stewarding his oak-hickory woodland with a forest management plan, prescribed fire, and invasive species removal.

Larry Cleverley was devastated when he learned that 30 acres of his family’s forest and pasture could be claimed by eminent domain to construct a new highway overpass. As a child, he walked there with his grandmother, searching for mushrooms and arrowheads. “My grandfather used to say that as long as he had that timber, he would never need tranquilizers or a psychiatrist.”

The clearing of the Mingo-area woodlands had begun a century before, as European settlers arrived and set up farms. In the 1940s, Larry’s grandfather helped clear over 40 acres to grow crops. At that time, dynamite was used to help remove stumps from the ground. Larry recounted, “The family had just bought their first tractor–a John Deere B. My dad was sitting on the tractor, and a stump flew 50 feet in the air. My dad panicked. Instead of driving the tractor off, he ran away, and the stump broke the steering wheel on the brand new tractor.”

Forester Luke Gran helped Larry identify trees of timber value, such as this mature white oak, on land slated for construction.

Throughout the following decades, the Cleverley family refrained from clearing the remaining woodlands. Cattle grazed there, and trees were sometimes harvested to heat the wood-burning furnace that Larry’s parents had through his junior year in high school. As a young adult, Larry moved to Chicago and later to New York. Then, 22 years ago, he moved back to his family’s land to grow garlic, specialty greens, and other vegetables for Des Moines-area chefs and farmers markets.

Even with a demanding farming schedule, Larry found time for occasional walks beneath the wide-branching oaks and hickories. He noted, “Our friends from Des Moines, New York, and Chicago can’t believe they’re in Iowa when we go out to the woods. We love to go out there.”

In April of 2015, Larry received notice that the new highway overpass would be built, despite his efforts to block it. He had only a few months before the parcel would be seized and cleared. It included some of the oldest white and bur oak and shagbark hickory trees on the farm, and many black walnuts. He was sickened to learn that the Iowa Department of Transportation (DOT) contractors planned to pile and burn the trees.

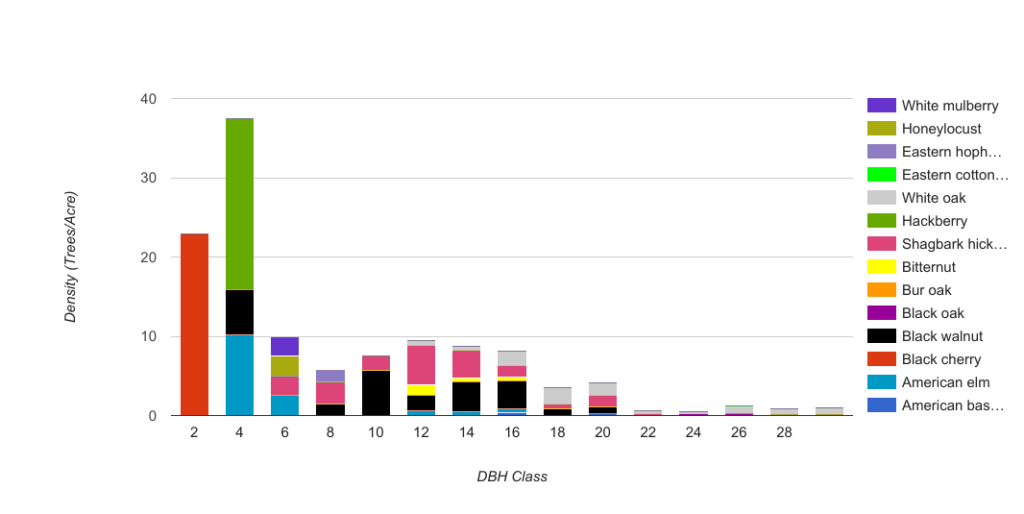

In forest management plans, data is gathered and synthesized to provide recommendations for management. This graph identifies the species by inches at diameter breast height (DBH) by density (trees/acre) within one of Larry’s woodland stands. The overstory (larger diameter) trees are mostly comprised of highly value species such as black walnut, white oak, and shagbark hickory. Few of these species appear in the regenerating (smaller diameter) trees. Management actions will be needed to sustain high quality habitat and timber production into the future.

“And at that time, I suppose, since we lost 30 acres of that timber, I truly realized how important it was to me,” reflected Larry. “It moved up the priority list.” When he called Luke from Prudenterra to discuss conducting a salvage timber sale, they ended up talking, not only about the 30 acres of soon-to-be DOT land, but the condition of the entire woodland. Larry hoped to return it to the condition it had been in a century before, when his grandparents had first moved onto the land.

A lot had changed in 100 years. Honeysuckle was creeping in from an adjacent park, where it had been planted in the 1980s in an ill-founded attempt to improve the habitat. The honeysuckle, along with another invasive—Russian olive—had been slowly taking over the understory, blocking native woodland wildflowers from sunlight. They now grew in impassable, wall-like thickets with large patches of bare soil beneath them.

Larry has seen blue lobelia and other native plants re-appear following the discontinuation of cattle grazing.

“We need to get rid of invasive species to get sunlight on the forest floor to get new trees to grow,” Larry clarified. “If we don’t do something about them, it’s just going to get worse. And [by managing invasive plants] we can hopefully make the timber into a revenue stream by having a fair amount to harvest.”

Larry decided to work with Luke to create a forest management plan to guide the restoration. It would help him and his siblings determine the value of the timber they owned, identify threats and opportunities for improving wildlife habitat, and receive recommendations to meet their goals for the land, including recreation and future timber harvests. To create the forest management plan, Luke first met with Larry and then collected data to evaluate each parcel.

The data revealed that 100 years of grazing had taken a toll on the woodlands. Many species of wildflowers that should have been present had disappeared from the landscape. In lieu of repairing the fences that had been cut open during the overpass construction, Larry decided to enroll all 80 acres of woodland in the Forest Reserve Program. This state program waives property taxes on qualifying woodlands in exchange for eliminating grazing and limiting timber harvests.

Goats are browsers, and prefer to eat to leaves of honeysuckle, autumn olive, and other invasive shrubs.

“In the years since we stopped grazing, we are seeing more blue lobelia, and patches I’ve never seen before of black-eyed susans and rushes around the creek,” recalled Larry. “Plus wild black raspberries, dutchman’s breeches, and jack-in-the-pulpit. I’m curious to see what else might appear.”

Throughout the process of restoration, Larry was inspired by the book Timberhill: Chronicle of a Restoration by Sibylla Brown. In it, Brown documents the reappearance of many species of plants and wildlife in her oak savanna remnant after prescribed burns were conducted. Larry knew that fire would be an important part of his restoration as well. “We would like to see some old native species appear like she has seen,” he explained. Plus, many non-native plants are killed or set back by fire.

All invasive shrub leaves within the goats’ reach were stripped bare following the prescribed browsing. The dense thicket was opened to chainsaws and prescribed fire for further management.

The first burn crept across the woodland in the fall of 2017. In spite of high humidity and milder-than ideal wind speeds, the low intensity burn took hold. Larry observed, “I’ve seen evidence that we killed some of the honeysuckle and the red cedars. I think with the prescribed burns it’s going to be a continual process.”

In August of 2018, a local business called Goats on the Go® delivered 200 four-legged restoration experts to a difficult-to-traverse area that was overgrown with honeysuckle. “We have a spot that’s adjacent to the park, “described Larry. “Luke calls it the wall–the honeysuckle is so thick in there. That is why we brought in the goats–to let them work on those ten acres.”

Soon, all honeysuckle and Russian olive leaves within reach of a goat on its hind legs had disappeared. A chainsaw crew could finally enter the area to cut and spray the tallest shrubs–ones that grew beyond the browsers’ reach. The combination of browsing and cutting would enable sunlight to reach the bare soil beneath the shrubs, allowing ground vegetation to grow enough to carry a prescribed burn.

Following goat browse, large honeysuckle and autumn olive shrubs were cut with chainsaws and the stumps were treated.

South-facing slopes will ready to burn by late fall or winter of 2018. The cooler north and east-facing slopes, on the other hand, will require another year of growth for a sufficient fuel load.

Woodland restoration is a multi-year process, but by eliminating continuous cattle grazing, killing invasive shrubs, and reintroducing prescribed fire, Larry is well on his way to restoring the woodland to what it was like over a century ago. The highway construction project propelled Larry into a role as woodland manager, and taught him a lot about the ecology of his family’s oak-hickory woodland. What he had not anticipated from the project was a significant archaeological discovery.

In advance of road construction, archaeologists from the University of Iowa brought over ground-penetrating radar to ensure that sites of cultural or historic value would not be disturbed. There, just eighteen inches below the surface of the soil, “They found a Woodland Indian pottery-making site from 400 AD–the most intact pottery making site from Woodland Indians they had ever seen.” Larry continued, “They also found an old hearth from the same time that had chestnut charcoal…[that] might have been from as far away as southern Illinois. They found a lot of hunting tools too, including a 4,000-year-old bone hunting knife.”

Although Larry lost 30 acres of woodland, the 80 acres that remain are now being managed to bring back native wildflowers, support wildlife, and enable oak and hickory trees to regenerate. More than ever, he enjoys spending time in the forest he once walked with his grandmother. This time, Larry brings with him the knowledge of its rich history that extends far beyond the last century.

Resources

Excerpts from Larry’s Forest Management Plan

Video: Goats Devour Invasive Shrubs in Larry’s woodland

Conducting an Ecological Timber Sale