Growing Chestnuts, Using Swales to Capture and Redirect Rainfall

Tony and LuAnn Colosimo installed earthworks to manage the flow of water and improve the productivity of agroforestry crops at Lucky Skunk Farm.

The steep topography at Lucky Skunk Farm near Albia led LuAnn and Tony to install swales–shallow trenches constructed on contour to capture rainwater.

After 30 years of living and working in Dallas, LuAnn and Tony Colosimo were ready for a change. “We examined our options, read a lot of books–probably hundreds–on retirement, how to live simply and sustainably, and how to change your business career to something you control yourself,” said LuAnn. In 2015, they finally made their move, landing in southeast Iowa, on 20 acres of land that had been in LuAnn’s family for more than 100 years.

Like most hilly ground typical of southern Iowa, the land had been previously used as a cattle pasture, but the Colosimos were interested in taking the farm in a new direction. As Tony and LuAnn networked locally, they found a community of knowledge about locally adapted specialty fruit and nut trees. Advisors recommended that they specialize in chinese chestnuts, because, “They are an in-demand product with a proven market,” explained Tony.

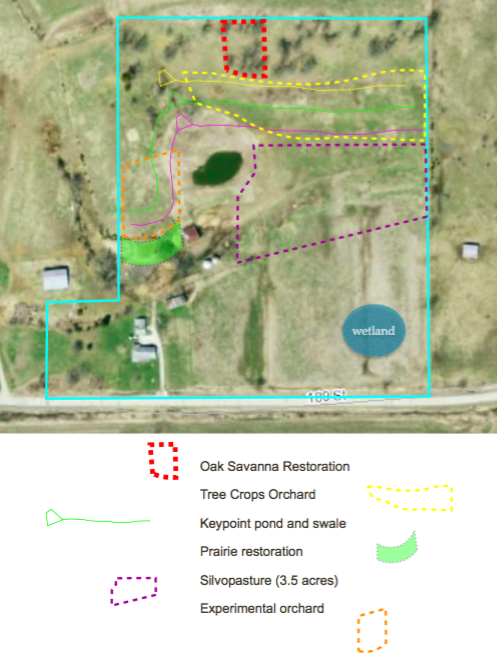

Aerial view of swales and pocket ponds shortly after construction, with captured rainfall visible.

After additional research, the Colosimos were convinced that chestnuts were indeed the right crop for them. Tony continued, “I love the idea of only planting once and harvesting for the rest of my life. They fall on the ground and you pick them up–its pretty simple.” LuAnn added, “They grow in our climate, and you can get nuts in just 5-7 years. Plus, they don’t require chemical spraying to prevent disease or insect damage. We started buying and eating them, and we love them–It’s like finding a beautiful surprise.”

As LuAnn and Tony started planning for chestnuts, they knew that water availability would be critical. Chestnut trees need regular rainfall or irrigation during seedling establishment and production to maximize yields and profit. “In most years we get enough rain, but it comes so fast,” said Tony. “And our ground is very steep,” added LuAnn. On their land, rainfall runs quickly from the highest point down to the lowest point, limiting the growth of vegetation in both places.

Tony and LuAnn refer to the area around the pocket ponds as the Amphibian Amphitheater. In the spring and summer, it roars with the calls of frogs.

With most rainfall running to the bottom of the slopes, Tony and LuAnn’s pasture and farmstead were flooding regularly. In a Land Walk with Prudenterra in early 2016, they identified water management as one of their top three goals. They wanted to “Better manage the flow of water on the land to heal eroded gullies, lessen flooding in the pasture, improve farmstead condition below the farm pond, and improve tree crop and pasture productivity.”

One way Tony and LuAnn hoped to accomplish this goal was with swales, which are shallow trenches, installed on contour. Swales capture rainfall high on the landscape, enabling the water to soak into the soil and be taken up by living roots. They are constructed at a 0% to 2% slope to passively redirect water from saturated valleys to dry hillsides. When the swales fill up in a heavy rain, excess precipitation flows to small earthen catchments called pocket ponds.

Swale were installed with a bulldozer and laser level (inside the trench) to set the desired depth and slope.

Swales and pocket ponds are part of a different water management approach than that used in traditional conservation practices, clarified LuAnn. “Often the way they have done terraces and farm ponds is to hold the water at the bottom of the hill.” In contrast, “Swales hold water throughout the land so it all can be watered rather than directing it down to a pond at the bottom of the basin. It’s about usability as well as conservation.”

In the summer of 2016, LuAnn and Tony partnered with Prudenterra to implement the design, layout, and installation of the earthworks. It was Prudenterra’s inaugural swale construction project, and, as Tony recalled, “We didn’t understand how different they were until the first bulldozer operator came out and built a terrace.” Fortunately, Prudenterra connected with a second bulldozer operator who understood the concept immediately, and in just a few days, swales and pocket ponds stretched across about 5 acres.

The trees at Lucky Skunk Farm connect LuAnn and Tony’s family to the farm. Each member planted and labeled their own tree so they can watch it grow.

With the swales and ponds in place, Tony and LuAnn planted 200 chestnuts and 200 pawpaws in the fall. The following summer brought a drought to Lucky Skunk Farm, which was an excellent opportunity to test the impact of passive water management on the chestnut seedlings. “Fortunately the swales held water for the trees, and the trees withstood drought okay, although we still had to water them some. The trees right below the swales were taller and leafier than those not underneath swales,” remembered Tony.

In spite of the drought, there were a couple of rain events, including one very heavy rain that measured at 6.6 inches. After that rain, they went out to take a look at the hillside. “It felt like not a drop of it left the property,” Tony recalled. “It all went into the ponds and swales, like it was supposed to,” observed LuAnn. “It was nice to see the ponds refilled. Nothing overflowed–it just held onto everything,” said Tony. “It was really cool–everything worked just the way we had planned.”

The New Vision Management Map from the Lucky Skunk Land Walk Report suggested the location of swales and pocket ponds, as well as other water management and agroforestry features.

As they witness the shifting weather patterns due to climate change, Tony says that he feels good about investing in the long-term resilience of their farm. “If we are going to have more heavy rain events, so be it, but we need to hold onto all of it. Whatever cockamaney ideas I have focused on, that 6.6 inches of rain made me feel justified in the decisions we’ve made.”

The Colosimos continue to hone their vision as they learn about new opportunities. They recently added a natural beekeeping enterprise, and are transforming their land into bee sanctuary by planting diverse species of native, flowering perennials. Next year, they will be planting two additional tree crops–persimmons and heartnuts–in the experimental orchard area.

Since moving to Iowa, LuAnn and Tony have started a new tradition–each fall, they host a chestnut roast at Lucky Skunk Farm. In just a few more years, it will be their own harvest browning over the flames.

Resources

Red Fern Farm – Nursery that breeds specialty fruit and nut trees in Iowa

Practical Farmers of Iowa – Grassroots, farmer-led organization and network

Prudenterra Earthworks – See more examples of earthworks that can improve water management